-

About

- About Listly

- Community & Support

- Howto

- Chrome Extension

- Bookmarklet

- WordPress Plugin

- Listly Premium

- Privacy

- Terms

- DMCA Copyright

- © 2010-2025 Boomy Labs

Jodie Taylor

Jodie Taylor

Listly by Jodie Taylor

Resources to guide reflective thinking and writing for students and teachers who aspire to be reflective practitioners. If you're new to reflective practice start with the featured resource. You can sort resources to suit your skill level and specific interests by clicking on the 'tags' function below.

Reflection is the act of directing your thoughts to focus your attention on a subject or an experience. While it can feel uncomfortable to formally reflect, reflection is something we do naturally. The skill with reflection is understanding how we do it and this is important as you are probably already reflecting informally every day without even realising it!

This short online lesson from Hull University will help you identify what reflective thinking is and how to evidence this in your reflective writing! I highly recommend anyone new to the idea of reflective practice to read through this and complete the activities.

This site is for people who want to reflect - maybe you already reflect or you have to do reflection in a course. Here you will find resources, models, and questions that can help you start your reflections as well as structuring them.

Reflection can happen anywhere and anytime and doesn’t require anything but yourself and your mind. Sometimes it can be helpful to capture it, whether that is in conversation, in writing, drawing, or something completely different.

The aim of this site is that you will have a look around and get a sense of what is useful when reflecting and then pick out the information and questions that work for you. You are your own expert.

However, if you are producing reflections for a course, make sure you know what they are asking for and follow their assessment criteria – they might have specific requirements.

In either case, reflective practice examines our thoughts, actions and experience and ask why they happened that way with the goal of improving ourselves or our understanding. This is clearly seen in the definition found on the homepage of the Reflection Toolkit.

How can I make a difference in the world? What is “good change” and how do I contribute to it? What is reflective practice? Reflective practices are methods and techniques that help individuals and groups reflect on their experiences and actions in order to engage in a process of continuous learning. Reflective practice enables recognition of the paradigms – assumptions, frameworks and patterns of thought and behaviour – that shape our thinking and action.

This paper explores current ideas and debates relating to reflective practice. In the first two sections, I review key definitions and models of reflection commonly used in professional practice. Then, in the reflective spirit myself, I critically examine the actual practice of the concept, highlighting ethical, professional, pedagogic and conceptual concerns. I put forward the case that reflective practice is both complex and situated and that it cannot work if applied mechanically or simplistically. On this basis, I conclude with some tentative suggestions for how educators might nurture an effective reflective practice involving critical reflection.

Finlay, L. (2008). Reflecting on 'Reflective practice.' Discussion paper 52 prepared for the Practice-based Professional learning group and the The Open University's Centres for Excellence in Teaching and Learning. http://www.open.ac.uk/opencetl/resources/pbpl-resources/finlay-l-2008-reflecting-reflective-practice-pbpl-paper-52

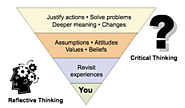

A great deal of your time university will be spent thinking; thinking about what people have said, what you have read, what you yourself are thinking and how your thinking has changed. It is generally believed that the thinking process involves two aspects: reflective thinking and critical thinking. They are not separate processes; rather, they are closely connected (Brookfield 1987).

Reflective self-questioning arises within the workplace when people are confronted with professional problems and situations. This paper focuses on reflective and' situated reflective' questions in terms of self-questioning and professional workplace problem solving. In our view, the situational context, entailed by the setting, social and personal/individual perspectives, is interactional. The supporting empirical data is drawn from our work with two groups in their tertiary phase of education: professional trainers within a large corporate organisation and para-professionals within a large college system; each embraces phenomenological principles. The discussions of situated reflective practice (SRP) entail those circumstances where change is visited upon the individual by forces outside their immediate control. The positive sense of SRP is that it can prepare an individual for anticipated change, and is therefore considered a method of change management. The situation acts as a catalyst for the thought.

So how do we build reflection time into our classroom routines? And how do we use that time to help our students better understand the creative process? Let’s find out.

This framework outlines the key elements and strategies to emerge from a research project by Amanda Moffatt, as part of her Doctor of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology. This online resource is an amalgamation of practitioners' voices, the historical development of reflective practice theory and Amanda's own professional reflection as a practitioner working in the field.

Following the integration of artistic disciplines within the university, artists have been challenged to review their practice in academic terms. This has become a vigorous epicentre of debates concerning the nature of research in the artistic disciplines. The special issue “On Reflecting and Making in Artistic Research Practice” captures some of this debate. This editorial article presents a broad-brush outline of the debates raging in the artistic disciplines and presents three discernible trends in those debates. The trends highlight different core questions: (1) Art as research: Can artistic practice represent forms of inquiry acceptable within academic settings? (2) Academically-attuned practice-led research: Can art practice and research practice cooperate as equal partners within the university context? (3) Artistic research: Can the academic notion of research be extended to include the unique results possible through artistic research? The articles in the special issue offer a discussable overview of the current stage in the development of artistic research, demonstrating how creative practice and research practice can come together.

Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2007). Practising Critical Reflection: A Resource Handbook. McGraw-Hill International.

Critical reflection in professional practice is popular across many different professions as a way of ensuring ongoing scrutiny and improved practice skills. This accessible handbook focuses on a description and analysis of the theoretical input as well as the approach involved in critical reflection. It also demonstrates some skills, strategies and tools which might be used to practise it. Accompanying the text is a website containing a variety of useful resources www.openup.co.uk/fook&gardner including, extracts from workshops, interviews and lectures, additional articles and readings and sample material for workshop preparation.

Reflective practice occurs when you explore an experience you have had to identify what happened, and what your role in the experience was – including your behaviour and thinking, and related emotions. This allows you to look at changes to your approach for similar future events. If reflective practice is performed comprehensively and honestly, it will inevitably lead to improved performances.

This chapter begins by attempting to review our understandings of critical reflection from literature drawn from different disciplines and professions, and from a range of countries as well. After a review of the types of literature and of the emerging understandings of the idea of critical reflection, the chapter also explores associated terms and ideas. In the last part of the chapter criticisms of critical reflection are reviewed, key issues outlined and suggestions for further directions are made.

White, S., Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2006). Critical reflection : a review of contemporary literature and understandings. In S. White, J. Fook, & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in health and social care. (pp. 3-20). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

What is reflective or reflexive writing?

Reflective writing is examining the knowledge acquired through reading or through an experience and making connections with other concepts that you have encountered in your learning.

Reflexive writing is a deeper, self-critical practice, that examines your underlying assumptions and attitudes and how they have been impacted by your learning. It is more personal than reflective writing.

This resource will step you through the what, why and how of reflection and includes practical lessons so you can test your skills.

Available also via SAE Ebrary subscription.

'This is an optimistic book which advocates and describes a different research paradigm to be practiced and developed. Read it and research!' - Lapidus 'She has achieved her aim of the book being readable and giving insight into the processes of doing research through the lenses of the personal stories of researchers, whilst still writing a text that could be used as a core research method text for those who are themselves becoming reflective researchers. No matter what your background in the social sciences this original book, grounded in the reflexive practice of an experienced teacher and researcher, is well worth checking out'. - Escalate 'Etherington (U, of Bristol) uses several narratives, including her own research diary and conversations with students and academics to demonstrate the way reflective research works in practice. Illustrating her points with poetry, paintings, metaphors and dreams, she suggests that recognizing the role of self in research can open up opportunities for creative and personal transformations. She also explores the use of reflexivity in counseling and psychotherapy practice and research.' - Book News This book raises important questions about whether or not researchers can ever keep their own lives out of their work. In contrast to traditional impersonal approaches to research, reflexive researchers acknowledge the impact of their own history, experiences, beliefs and culture on the processes and outcomes of inquiry. In this thought-provoking book, Kim Etherington uses a range of narratives, including her own research diary and conversations with students and academics, to show the reader how reflexive research works in practice, linking this with underpinning philosophies, methodologies and related ethical issues. Placing her own journey as a researcher alongside others, she suggests that recognising the role of self in research can open up opportunities for creative and personal transformations, and illustrates this idea with poetry, paintings and the use of metaphors and dreams. She explores ways in which reflexivity is used in counselling and psychotherapy practice and research, enabling people to become agents in their own lives. This book encourages researchers to reflect on how self-awareness can enrich relationships with those who assist them in their research. It will inspire and challenge students and academics across a wide range of disciplines to find creative ways of practising and representing their research.

Practice-led research is a burgeoning area across the creative arts, with studio-based doctorates frequently favoured over traditional research. Yet until now there has been little published guidance for students embarking on such research. This is the first book designed specifically as a pedagogical tool and is structured on the model used by most research programmes. A comprehensive introduction lays out the book's framework and individual chapters provide concrete examples of studio-based research in art, film and video, creative writing and dance, each contextualised by a theoretical essay and complete with references. More than a handbook, the volume draws on thinkers including Deleuze, Bourdieu and Heidegger in its examination of the relationship between practice and theory, demonstrating how practice can operate as a valid alternative mode of enquiry to traditional scholarly research. Taking pains to elaborate methodologies, contexts and outcomes, and emphasising the process of enquiry and its relationship to the research write-up or exegesis, this is an indispensable tool for educators and students.

This book addresses an issue of vital importance to contemporary practitioners in the creative arts: the role and significance of creative work within the university environment and its relationship to research practices. The turn to creative practice is one of the most exciting and revolutionary developments to occur in the university within the last two decades and is currently accelerating in influence. It is bringing with it dynamic new ways of thinking about research and new methodologies for conducting it, a raised awareness of the different kinds of knowledge that creative practice can convey and an illuminating body of information about the creative process. As higher education become more accepting of creative work and its existing and potential relationships to research, we also see changes in the formation of university departments, in the way conferences are conducted, and in styles of academic writing and modes of evaluation.

Reflective practice is a way of studying one's own experiences to improve the way one works. The act of reflection is a great way to increase confidence and become a more proactive and qualified professional.

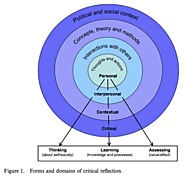

There is evidence to show that reflective techniques such as critical portfolios and reflective diaries can help students to consolidate and assess their learning of a discipline and its practices. Yet, there are also known drawbacks of critical reflection, including over selfcritical inspection and the infinite regress of reflection on action. This paper offers a theoretically informed model of critical reflection which encompasses different purposes (thinking, learning and assessment of self and social systems), together with different forms of reflection (personal, interpersonal, contextual and critical). Explicitly teaching critical reflection is a logical step towards students being able to recognise and negotiate complex ethical and professional issues. However, teaching critical reflection creates challenges for curricula design, assessment and professional development.

Smith, E. (2011). Teaching critical reflection. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(2), pp. 211 — 223.

Critical reflection is a highly valued and widely applied learning approach in higher education. There are many benefits associated with engaging in critical reflection, and it is often integrated into the design of graduate-level courses on university teaching, as a life-long learning strategy to help ensure that learners build their capacity as critical reflective teaching practitioners. Despite its broad application and learning benefits, students often find the process of engaging in critical reflection inherently challenging. This paper explores the challenge associated with incorporating critical reflection into a graduate course on University Teaching at the University of Guelph.

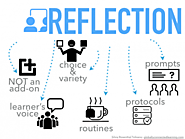

Reflection is an important component of the learning process. It can NOT be seen as an add-on, something to be cut if time is running short. We have all heard John Dewey’s quote: “We don’t learn from experience, we learn from reflecting on the experience”

Reflection also takes on an important role in documenting learning, blogging as pedagogy and formative assessment. Asking a teacher to simply “reflect” on a lesson taught or asking students to “reflect” on their learning, will often be met with blank stares. Being able to reflect is a skill to be learned, a habit to develop. Reflection requires metacognition (thinking about your thinking), articulation of that thinking and the ability to make connections (past, present, future, outliers, relevant information, etc.).

Developing strategies for methodical and systematic reflection and reflective practice in art, design and media education to improve development.

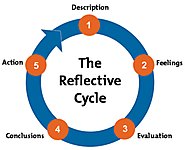

Many people find that they learn best from experience. However, if they don't reflect on their experience, and if they don't consciously think about how they could do better next time, it's hard for them to learn anything at all. This is where Gibbs' Reflective Cycle is useful. You can use it to help your people make sense of situations at work, so that they can understand what they did well and what they could do better in the future.

Critical reflection is a “meaning-making process” that helps us set goals, use what we’ve learned in the past to inform future action and consider the real-life implications of our thinking. It is the link between thinking and doing, and at its best, it can be transformative (Dewey, 1916/1944; Schön, 1983; Rodgers, 2002). Without reflection, experience alone might cause us to “reinforce stereotypes…, offer simplistic solutions to complex problems and generalize inaccurately based on limited data” (Ash & Clayton, 2009, p.26). Engaging in critical reflection, however, helps us articulate questions, confront bias, examine causality, contrast theory with practice and identify systemic issues all of which helps foster critical evaluation and knowledge transfer (Ash & Clayton, 2009, p. 27). While critical reflection may come more easily for some students than others, it is a skill that can be learned through practice and feedback (Dewey, 1933, Rodgers, 2002).

An effective mode of reflective practice and reflexivity is through personal professional narrative and story exploration. All professional and personal experience is naturally storied; telling or writing stories are prime human ways of understanding, communicating and remembering. Narratives of vital or key areas of professional experience can be communicated and explored directly and simply through expressive writing. These might be expressed fictionally; each story stands metonymically for that clinician’s practice. Uncritically accepted metaphors, with deep impact upon practice and experience, can also be noticed and evaluated. This article offers a richly exemplified argument for how confidential, carefully facilitated groups of professionals can be supported critically, yet gently examining their own and others’ practice, through written narrative and poetry. Implicit ethics and values can be perceived and enquired into, and professional identity and boundaries unthreateningly questioned and even challenged. Practitioners can gain greater observational powers and sense of authority over their work, and more of a grasp of its inherently complex political, social and cultural impact.

Dr Jodie Taylor is a Senior Lecturer, Postgraduate Supervisor and Curriculum Designer. Through the lens of critical pedagogy, Jodie’s praxis-orientated approach to education is guided by the desire to help students become aesthetically inspired, media literate, culturally sensitive, critical and creative thinkers.

She is the author of Playing it Queer: Popular Music, Identity & Queer World-making (Peter Lang 2012), and co-author of Redefining Mainstream Popular Music (Routledge 2013) and The Festivalisation of Culture (Ashgate 2014). She has published more than 30 scholarly articles & chapters on popular music, gender, sexuality and ageing; queer theory, youth culture and subcultural style; and ethical relations in ethnographic fieldwork.