-

About

- About Listly

- Community & Support

- Howto

- Chrome Extension

- Bookmarklet

- WordPress Plugin

- Listly Premium

- Privacy

- Terms

- DMCA Copyright

- © 2010-2025 Boomy Labs

Lauren Ford

Lauren Ford

Listly by Lauren Ford

Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson are revered to be two of the best writers in American Romanticism. Both of them were revolutionary in their ideals as to how a person should live their life and are considered to play pivotal roles in Transcendentalism. Sounds like a match made in bibliophile Heaven, right? Wrong. These two would have had more problems in their relationship than Tori Spelling and Dean McDermott. In this Listacle you will discover seven ways in which little ‘r’ romance would never work for these two mystics with opposite ideas about poetry, life, social critique, and you guessed it, love.

Walt Whitman was a man of many passions, traveling was one of them. Although he is not as traveled as self-proclaimed Percy Bysshe Shelley or Lord Byron, Whitman was a man about his country. Known to be an abolitionist, Whitman traveled along the Eastern countryside of America, keen to note the similarities in all men, women, and races that he came in contact with. In “Song of Myself” Whitman states, “I tramp a perpetual journey, (come listen all!) my signs are a rain-proof coat, good shoes, and a staff cut from the woods,” (pg. 1063). Here, he asserts himself as a seemingly humble traveler needing only, “a rain proof-coat, a pair of good shoes and a staff cut from the woods” in order to help him travel the world to be the spokesmen or the “poet of the people,” as he continues his never-ending journey to explore Whitman’s America and the people he meets. Thus, proving in Whitman’s philosophy that to be a well-rounded person (and poet) one must travel and explore the world with an open mind and heart.

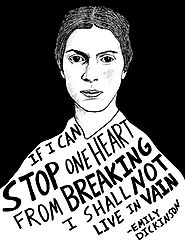

Emily, however, was a recluse. Nothing so trivial as travel struck her fancy because she stayed in her quiet family home in Amherst, Massachusetts. She did not find the need to indulge others with her poetry and often found the most comfort in silence of her own thoughts. In the poem known as #236 Dickinson states, “Some people keep the Sabbath going to Church- I keep it, staying at Home” (pg. 1196). Even her divinity towards her faith was best enjoyed kept from the outside world along with her life’s work. She did not find the need to dilute her thoughts for others to understand, instead everything within Emily’s work is personal and best kept in the mind of the reader than to be digested in the mind of the masses.

Emily grew up in a family with a good name in the community. Although they were not thought to be among the rich, her family was known to be a ‘respectable Christian’ influence in the community of Amherst. Emily herself never did commit herself to any one religion or Christian sect, but she was known to be very spiritual and being infatuated with botany would press fresh flowers in her bible. Dickinson saw the beauty in nature and the ways in which it can teach about life and death while reflecting her own views on religion. In poem 347 she writes, “No Blossom stayed away, In gentle deference to me – The Queen of Calvary-” (pg. 1200). This exert is a sample of one of the ways she used the never-ending cycle of nature to explain her personal philosophies. The blossoms are used to connect to life after death, connecting her inevitable death with the same view of impending doom like Jesus felt before Crucifixion on Calvary.

Walt might have grown up in a less than rich family, but his ego was something that no earthly riches could control, “Why should I pray? Why should I venerate and be ceremonious?” (pg. 1037). Lust and social inequalities were not the only thing on his mind, being the mind of all minds was in his mind. By trying to channel the thoughts of peoples into one he began to dream outside the realm of what was normal and what was Whitman. He states, “And I know that the hand of God is the promise of my own, And I know that the spirit of God is the brother of my own,” (pg. 1027). In this passage he embodies the essence of transcendentalism while bordering on sanctimonious nonsense. He wants to free the public from societal rules and regulations but goes too far and starts talking cray. By preaching for all to live in the present moment and forsake the chains of the past, he puts himself in a God-like position which begs the question of his mental health. One could go as far as comparing Walt Whitman in “Song of Myself” to Kanye West playing “Yesus.” Both men are indeed brilliant, but could you really take him in for more than ten minutes at a time?

__“The runaway slave came to my house and stopt outside, - through the swung half-door of the kitchen I saw him limpsy and weak and went where he sat on a log and lad him in and assured him, and brought water and fill’d a tub for his sweated body and bruis’d feet, And have him a room that enter’d from my own, and have him some coarse clean clothes.” (pg. 1030-1031).

_

This quote from “Song of Myself” is not just a wonderful example of Whitman’s philanthropic views on society, but also shows that he was willing to take in anyone whom needed his help. He was a transcendentalist servant, if you will, for the common man, the enslaved man, the poor man, and the outcasted man. Walt was never afraid to sit down with someone and have long discussions about life, philosophy, or any other organic human condition brought to his lips.

This open-door policy was anxiety inducing for Emily. Dickinson was a hermit and a home-body. It wasn’t just the thought of leaving the comfort of her own home that made her itchy, but it was also the idea of visitors which had her emotionally paralyzed. She would barely be seen in front of guests and often hid away in the construct of her own mind. Although she did have dinner with her brother and whomever he was with at the time, Emily preferred a life separate from the conventions held by other people. No one understood why this way of life was consuming for Emily, but there are thoughts looming by Dickinsonions that she might have been agoraphobic after tending to her terminal mother. However noble the reason, Emily would have never opened her personal chambers to strangers and would seldom choose to meet with the members of her own family.

Along with an affinity for entertaining, Whitman was not solely a man of words and not action. He writes in “Song of Myself” that, “Not a mutineer walks handcuff’d to jail but I am handcuff’d to him and walk by his side.” (pg. 1054). Whitman didn’t just talk about the change he wished to see in the society around him, but he also put himself at the front lines of suffering in order to see firsthand the struggles people whom are less fortunate have had to overcome. This is best shown when he went with his brother to Washington D.C. during the Civil War and became a bedside nurse for wounded soldiers. Mutilated bodies, lack of antiseptic, and the foul smell of blood and death in the air did not jade him like it had so many of the people he helped recover. Instead, it ignited a passion in his heart to continue with his work, believing that change started in the mind and soul of the individual.

Emily would no doubt value his brevity and courage, but she would not be one to join him on his quest to expose the world of all corrupt doings. That would mean getting out of her house and chancing to stain her white attire with foregone blood. She did, nonetheless, have a paralyzing fear of death and an overall sense of foreboding macabre when speaking on the subject. In poem 519 she states, “I heard a Fly buzz- when I died- … With Blue- uncertain – stumbling Buzz- Between the light- and me- And then the Windows failed0 and then I could not see to see-” (pg. 1207-8). Here, she sees the fly waiting for her to die so that it can lay its eggs within her dead flesh, proving that Emily is very aware of decomposition and what will happen to the human body after the heart stops beating. This terrified Emily and only served to force others that read her work to think about the way in which their body will be treated after death. Thus, returning to the blossoms of before, blooming despite the fall of death that will one day befall on us all.

“The young fellow drives the express-wagon, (I love him, though I do not know him;)” (pg. 1033)

Yes, you read the headline right. Walt Whitman was on many counts a lover of both men and women. Although it is not fair to label him a homosexual or bisexual, because the labels of our era were not available in the times of Whitman. Regardless of whatever label you deem appropriate for Walt, he liked men. Lots of men. In his personal accounts the longest relationships that he had were that of ones with men as his lovers. It is not clear if he was exclusive to only men, to strictly copulate with one sex would after all go against his neo-free love fixation on the human form living in a constant state of orgasmic rhythm with nature and the body.

Emily Dickinson could definitely be coined for her looming poems about death, however, there were also poems which demonstrated love and longing for a companion. In poem 269, known better as “Wild Nights,” Emily writes, “Futile- the winds- To a Heart in port- Done with the Compass- Done with the Chart!” (pg. 1197). Explaining that a heart in love can survive the longest and deadliest of storms because the finding of love was the hardest achievement of all. That a person in love doesn’t have to navigate through life any longer because the recognize their soul mate in another. To be fair to Emily, there are no accounts of any lovers (men or woman alike) were a part of Emily’s life, but her poems do indicate that at one point in time she felt a love that lived beyond her solitary like and stretched out into the world which she choose never to reacquaint.

Emily states in poem known as 788, “In the Parcel- Be the Merchant, Of the Heavenly Grace- But reduce no Human Spirit, To Disgrace of Price-” (pg. 1212). This poem proves that Emily refused to subject her work to be watered down or changed in order to appeal to the masses. Her poems were private and introspective. Her opinions on people whom published were less than kind associating their work with that of a material commodity and not a piece of the soul. It is not that she did not read other published writers, in fact, she took comfort in the written words of her predecessors such as Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emily did try publishing earlier on in her writing, however, she deterred from the path of notoriety and choose to write down her raw thoughts, pure and unedited by a need to please or appeal to someone other than herself.

Whitman, however, not so much. Whitman writes at the beginning of “Song of Myself,” “I celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume, For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” (pg. 1024). Here, Walt not only asserts that his work will be excepted by others, but also that it will become ageless and paramount to future generations. He isn’t wrong. Walt Whitman is still one of the highest rated American poets of this millennia, but it comes at a cost. Many people were originally put off by Whitman’s authoritarian style of poetry speaking for others as if it was himself. This dramatically narrowed his readership and also increased inquisitive minds because of the lude content. After being put on many banned books list, and forsaken by many churches, his proverbial congregation grew just as an immature moth is beaconed by the flame.

“I like a look of Agony, Because I know it’s true- Men do not sham Convulsion, nor simulate, a Throe-” Poem 339, (pg. 1199).

Finally, the biggest reason that Emily and Walt would never date is because there goals simply don’t match up. Emily died knowing that her poems would never be enjoyed by the masses while she was still alive. I would even venture far enough to say that the need for notoriety in her eyes was something she looked on others with great pity and disdain. In her poem 348 she states that, “I would not paint- a picture- I’d rather be the One, It’s bright impossibility, To dwell- delicious- on,-” (pg. 348). She, like writers such as Henry David Thoreau, did not want their work to take a place on the market like a materialistic object. She did not want to see her work for money, but instead, reveal her inner most thoughts and fears in the hymnal song of the soul, her poetry. When reading it, it is almost as provocative as Whitman’s because it feels like one is reading her diary. The tone should be that of stillness and pensive observation. What one feels when reading her poetry, is a foreboding era of unrest while she divulges her deepest and most guarded thoughts. It makes one become silent and pregnant with her short poetry as if it were as long and detailed as Whitman’s epic.

Good ol’ Walt never did snag a piece of that humble pie that of which was a daily diet for Emily. Instead Whitman craved for his work to be shown and noticed by everyone that dare take the time to absorb himself in his personal tirades. He even went as far as to send a copy of his anthology, Leaves of Grass to Ralph Waldo Emerson, (a proper and respected American Romantic at the time) and provided him with a review of his work written by none other than Walt Whitman himself. Balls of steel you say? Whatever the case may have been, Emerson loved it. He gave Whitman a thoughtful letter back and coined him as an up and coming star of the people’s voice. This only continued to feed Whitman’s ego and therefore controlled his thoughts to be just as controversial as Emily’s but with the volume turned up so high that no one can go without hearing what he has to say. He exclaimed in “Song of Myself,” “Unscrew the locks from the doors! Unscrew the doors themselves from their jambs! Whoever degrades another degrades me. And whatever is done or said returns at last to me.” (pg. 1041). Whitman is the center of his world and hopes to be invited to the center of the reader’s world as well. Perhaps the word invited is too polite for Whitman, maybe the correct term is that Whitman would inveigle himself into the center of the reader’s world and orchestrate a massive reboot to over whelm and over indulge the senses.